Scientists 3D-Print Human Organ Tissue in Breakthrough That Could Help End the Transplant Crisis and Save Lives

Each year, tens of thousands of people in the United States undergo life-saving organ transplants, but the number of patients waiting continues to far exceed the number of available donors. Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University say a promising solution may lie not in finding more donors, but in creating organs in the lab — using advanced bioprinting technology to construct living tissue layer by layer.

The university’s scientists have received a $28.5 million award from the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health to develop a transplantable 3D-printed liver patch. The initiative – known as the Liver Immunocompetent Volumetric Engineering (LIVE) project – aims to create living liver tissue that can temporarily take over core functions, giving a failing organ enough time to regenerate.

Instead of replacing the liver, the engineered tissue would support it for about two to four weeks, buying crucial time and reducing the need for full transplants.

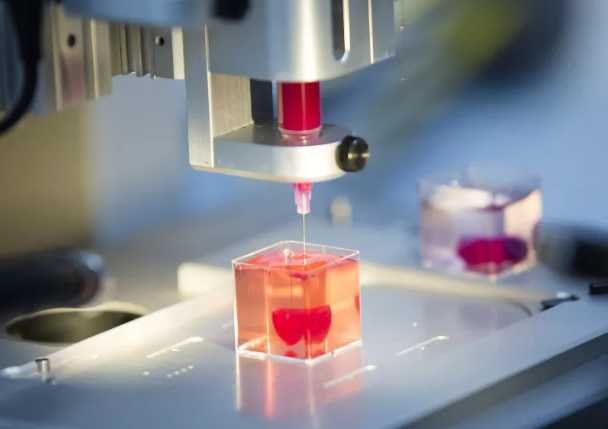

At the center of the work is the Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels, or FRESH, platform. Developed at Carnegie Mellon, FRESH allows researchers to print soft biological materials – such as collagen and living cells – into finely detailed, three-dimensional scaffolds that mimic complex human tissue structures.

Earlier studies by the same lab demonstrated that FRESH can produce vascularized pancreatic-like tissue, showing the system’s potential to model diseases such as Type 1 diabetes. The new challenge is scaling that approach to something much larger and more functionally demanding: the liver.

Unlike approaches that rely on genetically modified pig organs, the Carnegie Mellon project begins entirely with human biological materials. The printed tissues incorporate hypoimmune cells – engineered to act as universal donors – along with human collagens and other structural proteins.

The goal is to make the tissue inherently immune-compatible so that recipients do not need to take immunosuppressant drugs. “The challenge is really the immune system,” said project lead Adam Feinberg. “We are going to be using hypoimmune cells, which are engineered to be universal donors, so anyone can have the cells and tissues we are building without needing to take immune suppression.”

The wider field of transplantation research is moving in several directions at once. Recent advances include reviving organs after death using perfusion systems that restore circulation and oxygen, and extending the viability of donor organs outside the body.

Other teams are experimenting with genomic editing to create animal organs compatible with human biology; last year, a surgical team in China transplanted part of a pig’s liver into a living patient. Feinberg’s team, however, is steering toward a wholly human, biomanufactured solution.

The potential applications of FRESH bioprinting extend beyond emergency liver repair. The precision and cell-friendly environment of the process make it viable for constructing other complex tissues, such as the kidney, pancreatic, or even cardiac structures.

A 2025 study published in Science Advances by Feinberg’s group suggested that the same fundamentals used to print liver tissue could also power organ-on-a-chip systems for drug testing or disease modeling.

If successful, the LIVE project could mark a turning point in regenerative medicine, transforming organ replacement into organ repair and easing pressure on transplant waiting lists. For now, the next phase will test whether printed biology can meet the demands of the body’s most metabolically complex organ.